June Almeida & The Discovery of the First Human Coronavirus

By the bioMérieux Editors | Reading time: 3 min

PUBLICATION DATE : FEBRUARY 11, 2023

In 1966, Dr. David Tyrell was having trouble identifying a virus in a sample that he had collected from a sick schoolboy in Surrey, England. At the time, detecting a virus in tissue samples was painstaking work—samples were often cluttered with cellular debris, and viral particles were few and far between.

This particular flu-like virus, which Dr. Tyrell’s research team at the Common Cold Unit in Salisbury, Wiltshire labeled B814, was proving especially resistant to laboratory cultivation. In a last-ditch effort to identify the virus, Dr. Tyrell sent it to a laboratory at St. Thomas’ Hospital in London, where a young virologist was pioneering techniques in electron microscopy. “We were not too hopeful but felt it was worth a try,” Tyrrell wrote in his book, published in 2002, Cold Wars: The Fight Against the Common Cold.

The pioneering virologist was June Almeida, recently recruited to St. Thomas’ Hospital. Almeida’s journey into the field of virology was unusual. Born in 1930 and raised in a tenement building in Glasgow, Scotland, Almeida and her family had little money. Although she was a brilliant student with ambitions to attend university, her family’s limited resources led her down a different path. Instead, she dropped out of school in 1947, at the age of 16, and began working as a lab technician at Glasgow Royal Infirmary. There, she used microscopes to analyze tissue samples. Her work soon took her to London, where she performed a similar role at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital. She then married an artist and emigrated to Canada, where there happened to be a vacancy in the Ontario Cancer Institute in Toronto for an electron microscopy technician.

While working in Canada, Almeida perfected a technique known as negative staining. The technique uses dense metal, such as phosphotungstic acid, to increase the contrast in images. Her skills soon became apparent, and she co-authored many scientific publications related to the identification of the structure of viruses. At the time, it was easier to gain scientific recognition without a university degree in Canada than in Britain.

Almeida’s impeccable technique in electron microscopy was what gave Dr. Tyrell the small hope that she might be able to identify the virus that had stymied his research team. He shipped specimens to her that had been infected with B814, as well as common flu and herpes viruses to act as controls. Tyrrell had been informed that Almeida was “seemingly extending the range of the electron microscope to new limits.” However, he wasn’t overly expectant because the general belief at the time was that the electron microscope could only detect viruses in concentrated samples. The B814 specimens didn’t meet those criteria.

Despite Tyrrell’s uncertainty, Almeida not only found virus particles in the B814 specimen but was able to create clear images of them as well. On examining the results of Almeida’s work, Dr. Tyrell wrote that she [Almeida] , “exceeded all our hopes! She recognized all the known viruses, and her pictures revealed the structures beautifully. But, more importantly, she saw virus particles in the B814 specimens!”

Almeida also remembered seeing two viruses earlier in her research that appeared very similar in structure to B814. She had found one of them while looking at bronchitis in chickens and the other while studying hepatitis liver inflammation in mice.

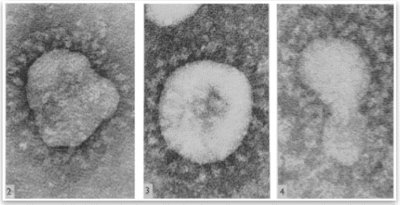

The paper she had written about both discoveries was rejected because reviewers could not decipher if the images were poor-quality pictures of influenza or something else. However, the images of the new B814 virus clearly revealed that it was surrounded by a halo-like structure, reminiscent of a solar corona. This led Almeida, Dr. Tyrrell, and their teams to coin the name, “coronavirus,” for the newly discovered family of viruses. B814 was the first coronavirus found to infect humans, but Almeida’s discovery of the coronavirus family went largely unremarked at the time. For the most part, coronaviruses were seen as a serious threat only to animals, and not to humans.

Over the course of her career, Almeida was best known for capturing the first image of the rubella virus and determining that there are two distinct components to the hepatitis B virus. In doing so, she pioneered a technique called immune electron microscopy, in which virus preparations are mixed with antibodies. The antibodies make it possible for the viruses to be seen clumped around them. Almeida passed her methods on to other virologists, including Albert Kapikian, who used immune electron microscopy at the National Institutes of Health to discover norovirus—a virus that frequently infects the gastrointestinal tract and accounts for about half of all food-borne illness.

Almeida’s contributions to the field of virology are immeasurable. Besides her discovery of the coronavirus family, she pioneered and perfected multiple techniques that have resulted in huge strides in viral imaging and diagnosis. Her imaging work also appears in numerous scientific textbooks and articles. Almeida died in Bexhill, England, on Dec. 1, 2007, at the age of 77.

SHARE THIS:

- Infectious Diseases

< SWIPE FOR MORE ARTICLES >